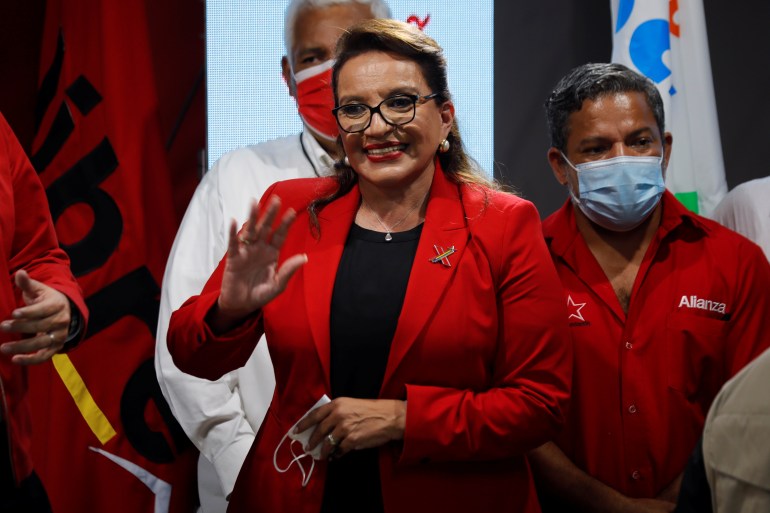

Tocoa, Honduras – Amid allegations that an elite Honduran police force colluded with a notorious gang while carrying out death-squad activities, observers are asking whether the administration of President Xiomara Castro has the political power or will to reform the country’s security forces.

According to an investigation last month by Honduran journalists, the National Anti-Gang Police Force and military police conducted extrajudicial executions and torture, while planting evidence and working in collusion with MS-13, the most prominent street gang in Honduras.

“Cases were fabricated, evidence was planted, and false positives were created in exchange for bribes,” said Wendy Funes, who runs Reporteros de Investigacion, the media outlet that uncovered the allegations. The police squad was “embedded in the Honduran state [and] existed to execute people”, she told Al Jazeera.

Despite newly elected President Castro’s pledge to demilitarise society, her administration has confirmed that military police – widely seen as a corrupt pet project of former President Juan Orlando Hernandez – would continue to operate on the streets. Jose Manuel Zelaya, Castro’s nephew and defence secretary, said the unit would be “directed towards fighting drug trafficking”, although he did not specify how this differed from its original stated mission.

Castro has sought to give the National Police, as opposed to the military, more control over the country’s security forces. Last month, her administration announced that the notorious anti-gang unit would be replaced by a heavily revised force, including members of the National Police and state prosecutors who specialise in organised crime.

These changes come amid a recalibration of the criminal underworld and corrupt factions in Honduras following the recent extradition of Hernandez to the United States, said Juan Martinez D’Aubuisson, an anthropologist and investigative journalist who studies violence in Honduras.

“This is a period of elimination, a period of transformation, in which [different groups] are competing to fill in the gaps left by the old power structures and criminal structures,” he told Al Jazeera. “These competitions are always violent … We’re going to see lots of problems within the police, within different state institutions, and within the criminal underworld.”

Violence and extortion

Honduras has consistently been ranked as one of the most violent countries in the world outside of a declared war zone. Hundreds of thousands of Hondurans have fled to the United States, seeking to escape violence and extortion.

A key strategy deployed by the Honduran state to fight street gangs in recent years has been the so-called Iron Fist approach, a form of hardline policing popular in Central America that has been associated with torture, summary executions and failure to reduce violence in the long term.

The policy was embraced by Hernandez, who created more than a dozen hybrid military-police forces to patrol the country’s conflict-ridden streets. The former president has since been arrested and extradited to the US to face drug trafficking charges.

Among the troubling cases highlighted by Reporteros de Investigacion was that of a 20-year-old man killed last August in Tegucigalpa. After the National Anti-Gang Police Force allegedly carried out an early-morning raid to seek an extortion payment, the young man fled to a nearby house, where officers chased him down and a single shot was heard.

In another case, a young man was allegedly detained by members of the force in the northern city of San Pedro Sula and was heard screaming: “Aunt Elia, help me!” He was never seen again.

Torture was not uncommon, according to the investigation, which notes that one man was detained, had a black plastic bag placed over his head and tape over his nose, and was submerged repeatedly in a tub of water in an effort to extract information. He was then allegedly made to sign a confession document before being trotted out in front of the media.

The head of the National Police, Gustavo Sanchez Velasquez, in June acknowledged abuses by the National Anti-Gang Police Force during a segment on Honduran national television, promising: “We are going to transform it, because we’ve found an institution that violated human rights. We’ve found an institution that brought false testimonies to different institutions. We’ve found an institution that planted evidence.”

Some Hondurans remain unsure as to whether Velasquez can live up to those promises. Leonel George, a human rights defender from Tocoa, told Al Jazeera it would present a “really difficult” task.

“He’ll have to purge half the police, or even more,” George said. “It’s possible that he’ll advance in terms of extraditing corrupt leaders involved in narco-trafficking. But I think it’ll be harder in terms of security – getting rid of police death squads. The problem is so huge.”

Adilia Castro, a human rights worker from the department of Colon, told Al Jazeera that so far, nothing has fundamentally changed with the country’s security framework: “What we’re seeing now is an attempt to lower the profile of how the state security forces operate.”

Neither the National Anti-Gang Police Force nor its successor agency responded to questions from Al Jazeera.

‘Terror is a tool’

Last month, outside a posh nightclub in central Tegucigalpa, a squad of masked gunmen with automatic weapons jumped from a Volkswagen Amarok and forced four men – among them Said Lobo, the son of former President Porfirio Lobo – against the wall at gunpoint, then executed them in a mass killing that shocked the nation.

MS-13 was accused of being complicit in the crime and police also came under scrutiny, as the assailants were wearing uniforms resembling those of the anti-gang squad (although the squad has denied any connection to the incident, citing differences in the bulletproof vests they wore).

Two years earlier, gunmen dressed in what appeared to be the anti-gang squad’s uniforms helped to free a leading MS-13 leader from a Honduran courthouse, killing four security guards in the process.

Lobo’s killing – which came amid a steady rise in mass killings this spring – presaged an order by the Castro government that military police accompany National Police in all operations. Castro has yet to address the apparent contradiction of the order with her original message of demilitarising the country.

Funes believes the incident might point to a destabilisation campaign connected to corrupt powers who want to keep those security forces in the streets.

“Terror is a tool for militarising public security,” she said. “It’s not a coincidence that, a few days after the killing of [Porfirio] Lobo’s son … the president announces the military police will return to the streets. They were still, in reality, in the streets. But the point was to create a media effect: they wanted to sell the notion of the remilitarisation of society.”